News

How Does a Solenoid Valve Work: Complete Operating Guide

The Core Operating Principle of Solenoid Valves

A solenoid valve operates through electromagnetic force that moves a plunger or armature to open or close fluid flow passages. When electrical current flows through a wire coil, it generates a magnetic field that pulls a ferromagnetic core into the coil, mechanically actuating the valve mechanism. This process occurs in milliseconds, typically between 10-150ms depending on valve size, making solenoid valves ideal for rapid, automated fluid control in systems ranging from residential sprinklers to industrial chemical processing.

The fundamental advantage of solenoid valves lies in their ability to convert electrical signals directly into mechanical valve motion without requiring external power sources like pneumatic or hydraulic actuators. This direct-acting mechanism enables precise, repeatable control with cycle lives exceeding 1 million operations in properly maintained industrial applications.

Key Components and Their Functions

The Electromagnetic Coil Assembly

The solenoid coil consists of hundreds or thousands of copper wire windings wrapped around a tube or bobbin. When voltage is applied, the coil generates a magnetic field with strength proportional to the number of turns and current flow. Standard industrial coils operate at 12V DC, 24V DC, 110V AC, or 220V AC, with power consumption ranging from 2 to 25 watts depending on valve size and application.

The coil housing, typically made from thermoplastic or metal, protects the windings from environmental exposure and provides heat dissipation. Continuous-duty coils are designed to handle sustained energization without overheating, while intermittent-duty coils are rated for shorter activation periods with cooling intervals.

Plunger or Armature Mechanism

The plunger, constructed from ferromagnetic materials like iron or steel, serves as the moving element that responds to the magnetic field. In the de-energized state, a return spring holds the plunger in its normal position—either open or closed depending on valve configuration. When energized, the electromagnetic force overcomes spring tension, typically requiring force ranges from 5 to 500 Newtons based on valve pressure rating and orifice size.

The plunger connects to a seal or disc that makes contact with the valve seat, creating a leak-tight closure. Modern designs use materials like PTFE, NBR, or EPDM for seals, selected based on fluid compatibility and temperature requirements ranging from -10°C to 180°C.

Valve Body and Flow Path

The valve body contains inlet and outlet ports with internal passages that direct fluid flow. Common materials include brass, stainless steel 316, aluminum, and engineered plastics, chosen for corrosion resistance and pressure handling capability. Standard bodies accommodate pressures from 0 to 250 bar (3,625 psi), with specialized high-pressure variants reaching 500 bar.

Port configurations include 2-way (inlet/outlet), 3-way (inlet with two outlets or two inlets with one outlet), and multi-port designs for complex flow routing. Connection types vary from threaded NPT or BSP fittings to flanged or compression fittings for different installation requirements.

Step-by-Step Operating Sequence

De-Energized State

In the default de-energized condition, no electrical current flows through the coil. The return spring maintains the plunger in its resting position, determining whether the valve is normally closed (NC) or normally open (NO). For normally closed valves, the spring force keeps the seal pressed against the seat, blocking fluid passage. Normally open valves feature spring positioning that allows fluid flow when unpowered.

This fail-safe characteristic is critical for safety applications. For example, emergency shutdown systems typically use normally closed valves that automatically stop flow during power failures, while cooling water systems may employ normally open valves to ensure continuous flow if control power is lost.

Energization and Valve Opening

When voltage is applied to the coil terminals, current flows through the windings, creating a magnetic field that magnetizes the plunger. The resulting electromagnetic force pulls the plunger toward the center of the coil against spring resistance. This movement lifts the seal from the seat or shifts it to redirect flow, completing the state change in 10-50 milliseconds for small valves or up to 150 milliseconds for large industrial units.

The strength of the magnetic force follows the equation F = (N × I)² × μ₀ × A / (2 × g²), where N is the number of coil turns, I is current, μ₀ is magnetic permeability, A is the pole face area, and g is the air gap. This relationship explains why inrush current during initial energization can be 3-5 times higher than holding current as the air gap decreases.

De-Energization and Valve Closing

When electrical power is removed, the magnetic field collapses almost instantaneously, releasing the plunger. The return spring immediately drives the plunger back to its original position, reseating the seal and returning the valve to its normal state. Response time during closing is typically faster than opening, often 5-30 milliseconds, due to spring force acceleration and reduced resistance.

Proper spring sizing ensures reliable closing even when system pressure opposes plunger movement. Engineers calculate required spring force by adding closing force requirements, friction losses, and a safety factor of 1.5-2.0 to guarantee positive sealing under all operating conditions.

Direct-Acting vs. Pilot-Operated Designs

Direct-Acting Solenoid Valves

Direct-acting valves use electromagnetic force to directly move the seal against the seat without assistance from fluid pressure. These valves work effectively at zero differential pressure and can operate with no minimum pressure requirement, making them suitable for applications like gravity-fed systems or vacuum service.

The tradeoff for this versatility is size limitation. Because the solenoid must generate all closing/opening force, direct-acting valves are typically limited to orifice sizes below 20mm (3/4 inch) and flow coefficients (Cv) under 5.0. Larger orifices would require impractically large, power-hungry coils.

Pilot-Operated Solenoid Valves

Pilot-operated designs use a small solenoid to control a pilot orifice, allowing system pressure to assist in actuating the main valve seal. This pressure-assisted operation enables much larger flow capacities with relatively small coils. The mechanism works through a diaphragm or piston that separates an upper chamber from the main flow path.

In the closed position, fluid pressure equalizes above and below the diaphragm through a small bleed hole, but the larger surface area on top creates net closing force. When the solenoid opens the pilot orifice, it vents the upper chamber, creating pressure differential that lifts the diaphragm and opens the main passage. This amplification effect allows pilot-operated valves to handle orifice sizes up to 100mm (4 inches) or larger with Cv values exceeding 100.

| Feature | Direct-Acting | Pilot-Operated |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Pressure | 0 bar (vacuum capable) | 0.5-1.0 bar required |

| Maximum Orifice Size | 20mm (3/4 inch) | 100mm+ (4+ inches) |

| Power Consumption | 2-10 watts | 3-15 watts |

| Response Time | 10-50 ms | 50-150 ms |

| Fluid Cleanliness | Less sensitive | Requires filtration |

Electrical Control Principles

AC vs. DC Coil Operation

AC solenoid coils experience continuous magnetic field reversal at line frequency (50 or 60 Hz), creating a pulsating force on the plunger. To prevent audible buzzing or chattering, AC designs incorporate a shaded pole—a copper ring around part of the pole face that creates a phase-shifted secondary magnetic field, maintaining continuous holding force between current reversals.

DC coils provide smooth, constant magnetic force without pulsation, offering quieter operation and longer service life due to reduced mechanical vibration. However, DC coils exhibit higher inrush current, often 4-5 times the holding current, requiring careful consideration of power supply capacity and wire sizing. Many DC solenoids use pulse-width modulation (PWM) control to reduce holding power by 50-70% after initial actuation.

Voltage Tolerance and Coil Protection

Solenoid coils typically function across a voltage range of ±10% of nominal rating, though operation outside this range affects performance and lifespan. Undervoltage conditions below 85% of nominal may prevent complete actuation or cause overheating due to increased current draw in the partially opened position. Overvoltage above 110% accelerates insulation breakdown and can cause coil burnout.

Protection devices commonly integrated into solenoid circuits include:

- Flyback diodes or suppressor diodes across DC coils to dissipate inductive voltage spikes during de-energization

- Varistors or RC snubbers for AC coils to limit transient voltages

- Thermal fuses or thermistors to prevent overheating damage

- LED indicator lights to confirm energization status

Pressure Differential and Flow Considerations

Minimum and Maximum Pressure Ratings

Every solenoid valve operates within defined pressure limits. The maximum operating pressure (MOP) indicates the highest system pressure the valve can withstand without leakage or structural failure, typically ranging from 10 bar (145 psi) for general-purpose valves to 250 bar (3,625 psi) for high-pressure applications. Exceeding MOP can cause seal extrusion, body cracking, or plunger deformation.

Pilot-operated valves require minimum differential pressure to function correctly, usually 0.5-1.0 bar (7-15 psi). Below this threshold, insufficient pressure differential prevents proper diaphragm actuation, causing incomplete opening or failure to close. Applications with variable or low pressure require direct-acting designs that operate at zero differential.

Flow Coefficient and Sizing

The flow coefficient (Cv) quantifies valve capacity, defined as the flow rate in gallons per minute of 60°F water that creates a 1 psi pressure drop across the valve. Proper valve sizing ensures adequate flow without excessive pressure loss or velocity-induced erosion. Undersized valves create flow restrictions, while oversized valves cost more and may operate unstably at low flows.

The sizing equation Q = Cv × √(ΔP / SG) relates flow rate (Q in GPM), pressure drop (ΔP in psi), and specific gravity (SG). For example, a valve with Cv = 2.0 passing water with 10 psi pressure drop delivers 6.3 GPM. Gas and steam applications require modified equations accounting for compressibility and temperature effects.

Common Valve Configurations and Applications

2-Way Solenoid Valves

Two-way valves feature one inlet and one outlet, functioning as simple on/off flow control devices. They operate in either normally closed or normally open configurations, with NC valves being far more common, representing approximately 80% of solenoid valve applications. These valves excel in applications requiring positive shutoff, such as water supply control, fuel dispensing, or pneumatic system isolation.

3-Way Solenoid Valves

Three-way valves contain three ports for flow diversion or mixing applications. Common configurations include:

- Universal/diverting type: One inlet, two outlets—routes flow to outlet A when de-energized, to outlet B when energized

- Mixing type: Two inlets, one outlet—connects inlet A when de-energized, inlet B when energized

- Exhaust type: One inlet, one outlet, one exhaust—used in pneumatic systems to pressurize or vent actuators

Three-way valves enable applications like dual-temperature control systems, cylinder actuation without separate exhaust valves, or alternating flow between two circuits using a single valve instead of two 2-way units.

Real-World Application Examples

Solenoid valves serve diverse functions across industries:

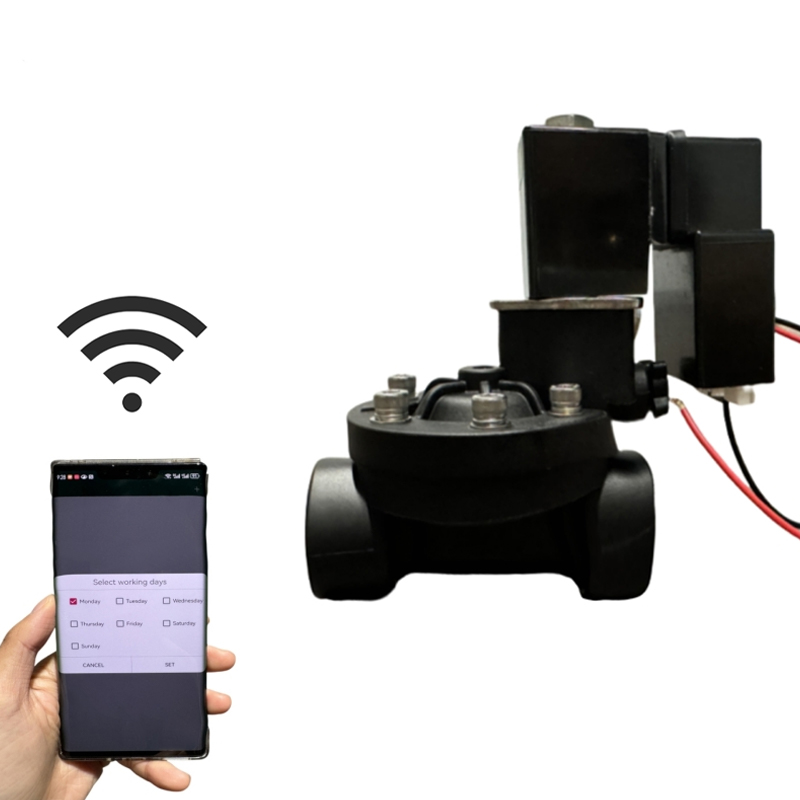

- Irrigation systems use 24V AC normally closed valves controlled by timers to automate zone watering

- Washing machines employ multiple solenoids for hot/cold water inlet control and drain valve operation

- Pneumatic automation systems utilize manifold-mounted 3-way valves operating at response times under 20ms for high-speed cylinder control

- Medical equipment requires FDA-compliant valves with stainless steel bodies and EPDM seals for oxygen and medical gas delivery

- Chemical processing facilities use PTFE-sealed, explosion-proof solenoids for corrosive and hazardous fluid handling

Maintenance and Troubleshooting

Common Failure Modes

Solenoid valve failures typically stem from predictable causes:

- Coil burnout: Results from overvoltage, inadequate cooling, or continuous duty beyond rating—accounts for approximately 35% of failures

- Seat wear and leakage: Caused by contamination, excessive cycling, or chemical incompatibility—represents about 30% of failures

- Plunger sticking: Occurs due to contamination, corrosion, or mineral buildup—comprises roughly 20% of issues

- Diaphragm rupture: In pilot-operated valves, caused by pressure surges or material degradation—accounts for 15% of failures

Preventive Maintenance Practices

Implementing routine maintenance extends valve life and prevents unplanned downtime:

- Install upstream filtration at 40-100 micron level to prevent contamination of pilot orifices and seating surfaces

- Verify supply voltage remains within ±10% of coil rating using periodic measurements

- Monitor coil temperature during operation; excessive heat indicates voltage problems or duty cycle issues

- Test manual override mechanisms monthly to ensure emergency operation capability

- Replace seals and diaphragms according to manufacturer schedules, typically every 2-5 years depending on cycle count

- Flush systems before valve installation to remove construction debris and welding slag

Diagnostic Testing Procedures

When troubleshooting malfunctioning valves, systematic testing identifies root causes:

First, verify electrical supply by measuring voltage at the coil terminals during energization. Proper voltage with no valve operation suggests mechanical binding or coil failure. Test coil resistance with a multimeter; values deviating more than 10% from nameplate specifications indicate winding damage. Listen for audible clicking during energization—presence confirms electromagnetic actuation, narrowing problems to mechanical binding or seal issues.

For persistent leakage, isolate the valve and verify system pressure remains within rated limits. Disassemble and inspect seals for cuts, wear, or deformation. Check seating surfaces for scoring or contamination particles. In pilot-operated valves, verify the pilot orifice remains clear by removing the coil assembly and observing flow through the bleed passage.

Selection Criteria for Optimal Performance

Choosing the appropriate solenoid valve requires evaluating multiple parameters simultaneously:

| Selection Factor | Key Considerations | Typical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Fluid Type | Material compatibility, viscosity, cleanliness | Water, air, oil, steam, chemicals |

| Pressure Range | Operating and maximum pressure | 0-250 bar typical |

| Flow Capacity | Required Cv, orifice size | 0.1-100+ Cv |

| Temperature | Fluid and ambient temperature limits | -10°C to 180°C standard |

| Electrical Supply | Available voltage, AC or DC | 12/24 VDC, 110/220 VAC |

| Duty Cycle | Continuous or intermittent operation | 100% or specified percentage |

| Response Time | Opening/closing speed requirements | 10-150 milliseconds |

Environmental factors also influence selection. Outdoor installations require weather-resistant enclosures rated IP65 or higher to prevent moisture ingress. Hazardous locations demand explosion-proof housings certified for specific gas groups and temperature classes. Food and pharmaceutical applications necessitate 3-A sanitary certifications and electropolished stainless steel construction.

Lifecycle cost analysis should include not only initial purchase price but also energy consumption, maintenance requirements, and expected service life. A higher-quality valve costing 30-50% more initially may deliver 2-3 times longer service life, resulting in lower total cost of ownership over the installation lifespan.

English

English Español

Español