News

What is a Solenoid Valve? Function, Types & Applications Guide

Understanding Solenoid Valves

A solenoid valve is an electromechanical device that uses electromagnetic force to control the flow of liquids or gases through a system. When electrical current passes through a coil wrapped around a metal core, it creates a magnetic field that moves a plunger or piston, opening or closing the valve passage. This automated control mechanism makes solenoid valves essential in countless industrial, commercial, and residential applications where precise fluid control is required.

The term "solenoid" refers to the cylindrical coil of wire that generates the magnetic field when energized. Combined with a valve body and internal sealing components, this creates a reliable, fast-acting valve that can be controlled remotely through electrical signals. Unlike manual valves that require physical operation, solenoid valves enable automated, programmable control of fluid systems with response times typically ranging from 10 to 100 milliseconds.

How Solenoid Valves Work

The operating principle of a solenoid valve relies on electromagnetic induction. The valve consists of several key components that work together to control fluid flow:

- Solenoid coil: When energized with electrical current, it generates a magnetic field

- Plunger (armature): A movable ferromagnetic core that responds to the magnetic field

- Valve body: Contains the fluid passageways and sealing mechanisms

- Spring: Returns the plunger to its original position when power is removed

- Seal or diaphragm: Prevents fluid leakage when the valve is closed

Direct-Acting Operation

In direct-acting solenoid valves, the plunger physically opens and closes the orifice. When the coil is energized, the magnetic field pulls the plunger upward (or pushes it downward, depending on design), opening the flow path. When power is removed, the spring returns the plunger to its original position, closing the valve. These valves can operate with zero pressure differential and are commonly used in applications up to 1 inch (25mm) in diameter.

Pilot-Operated Operation

Pilot-operated solenoid valves use system pressure to assist in opening and closing. The solenoid controls a small pilot orifice, and the pressure differential across a diaphragm or piston does the actual work of opening the main valve port. This design requires minimum pressure differential of 0.5 to 1 bar (7-15 psi) to function but can handle much larger valve sizes—up to 4 inches (100mm) or more—with relatively small solenoid coils.

Types of Solenoid Valves

Solenoid valves are classified based on several characteristics, including the number of ports, normal position, and operating principle.

By Port Configuration

| Type | Ports | Function | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Way | 2 (inlet, outlet) | Simple on/off control | Water dispensers, fuel cutoff |

| 3-Way | 3 (inlet, 2 outlets or 2 inlets, 1 outlet) | Diverting or mixing flow | Pneumatic cylinders, heating systems |

| 4-Way | 4 or 5 ports | Reversing flow direction | Double-acting pneumatic actuators |

By Normal Position

Normally Closed (NC): The valve remains closed when de-energized and opens when power is applied. This is the most common type, accounting for approximately 70-80% of solenoid valve installations. NC valves provide fail-safe operation in many applications, automatically shutting off flow during power failures.

Normally Open (NO): The valve stays open when de-energized and closes when energized. These are used where continuous flow is required and shutdown occurs only when activated, such as in emergency shutdown systems or cooling circuits that must maintain flow during power outages.

Bi-stable (Latching): These valves use a permanent magnet to hold position without continuous power. A momentary electrical pulse switches the valve state, where it remains until the next pulse. This design can reduce energy consumption by up to 95% compared to continuous-duty valves.

Key Specifications and Selection Criteria

Selecting the appropriate solenoid valve requires careful consideration of multiple factors to ensure reliable operation and longevity.

Fluid Compatibility

The valve materials must be compatible with the fluid being controlled. Common body materials include brass (for water and air), stainless steel 316 (for corrosive fluids), and plastic materials like PVC or PTFE (for highly corrosive chemicals). Seal materials range from NBR (nitrile) for general use to EPDM for hot water, FKM (Viton) for hydrocarbons, and PTFE for aggressive chemicals. Using incompatible materials can lead to seal degradation and valve failure within weeks or months.

Pressure and Temperature Ratings

Operating pressure must fall within the valve's rated range. Standard solenoid valves typically handle pressures from 0 to 10 bar (0-150 psi), while high-pressure models can operate up to 40 bar (580 psi) or more. Temperature ratings vary widely: general-purpose valves function from -10°C to +80°C (14°F to 176°F), while specialized high-temperature models can handle up to 180°C (356°F).

Flow Capacity and Cv Value

The valve must provide adequate flow for the application. Flow capacity is often expressed as the Cv (flow coefficient) value, which represents the flow rate in gallons per minute of 60°F water with a 1 psi pressure drop. For example, a valve with Cv = 2.5 will pass 2.5 GPM of water under these conditions. Undersized valves create excessive pressure drop, while oversized valves may not seal properly at low pressures.

Electrical Requirements

Common voltage options include AC (24V, 110V, 220V) and DC (12V, 24V) power supplies. AC valves are simpler and less expensive but consume more power and generate more heat. DC valves offer faster response times (10-20ms vs. 30-50ms for AC), quieter operation, and compatibility with electronic control systems. Power consumption typically ranges from 5 to 30 watts depending on valve size and type.

Common Applications Across Industries

Solenoid valves serve critical functions in virtually every industry that handles fluids or gases.

Industrial Automation and Manufacturing

In automated production lines, solenoid valves control pneumatic actuators, robotic systems, and material handling equipment. A typical automotive assembly plant may use over 10,000 solenoid valves to control welding robots, paint systems, and quality testing equipment. The fast cycling capability—some valves can operate millions of cycles—makes them ideal for high-speed manufacturing processes.

Water and Wastewater Treatment

Municipal water systems employ solenoid valves for automatic flushing, chemical dosing, and backwash sequences in filtration systems. Irrigation systems use solenoid valves controlled by timers or soil moisture sensors to automate watering schedules, potentially reducing water consumption by 30-50% compared to manual operation.

HVAC and Refrigeration

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems utilize solenoid valves for refrigerant flow control, condensate drainage, and hot water distribution. In commercial refrigeration, solenoid valves enable hot gas defrost cycles and capacity control, improving energy efficiency by 15-25% compared to mechanical controls.

Medical and Laboratory Equipment

Medical devices such as dialysis machines, anesthesia systems, and automated analyzers depend on precise solenoid valve control. These applications often require valves with FDA-approved materials, autoclavable construction, and leak rates below 1×10⁻⁶ mbar·l/s to ensure patient safety and measurement accuracy.

Automotive Systems

Modern vehicles contain 20-40 solenoid valves controlling fuel injection, transmission shifting, emission controls, and braking systems. Anti-lock braking systems (ABS) use rapid-cycling solenoid valves that can pulse 15-20 times per second to modulate brake pressure and prevent wheel lockup.

Installation and Maintenance Considerations

Proper installation and maintenance significantly impact solenoid valve performance and lifespan.

Installation Best Practices

- Install the valve with the solenoid coil in the vertical upright position when possible to prevent debris accumulation

- Ensure flow direction matches the arrow marked on the valve body—reverse installation can prevent operation

- Install upstream filtration to remove particles larger than 50 microns, which can damage seals or block orifices

- Provide adequate clearance above the valve for coil removal during maintenance

- Use thread sealant or tape appropriate for the fluid and avoid over-tightening, which can crack plastic bodies

Common Problems and Solutions

Valve fails to open: This often results from insufficient supply voltage (check for minimum 85% of rated voltage), debris blocking the orifice, or a burned-out coil. Testing coil resistance with a multimeter—it should read within 10% of the manufacturer's specification—can diagnose electrical failures.

Valve fails to close: Worn seals, damaged diaphragms, or foreign material preventing complete closure typically cause this issue. In pilot-operated valves, insufficient pressure differential can also prevent closing.

Leakage through valve: Seal deterioration from chemical incompatibility, excessive temperature, or normal wear requires seal replacement. Small particles lodged in the seat can often be cleared by cycling the valve several times or back-flushing.

Expected Lifespan

Service life varies dramatically based on application conditions. Under ideal conditions with clean fluids and moderate cycling, quality solenoid valves can achieve 1-10 million cycles or 5-10 years of continuous operation. However, dirty fluids, pressure spikes, or operation beyond rated specifications can reduce lifespan to months. Regular inspection and preventive maintenance—including cleaning, seal replacement every 2-3 years, and coil testing—maximizes valve longevity.

Advantages and Limitations

Key Advantages

- Fast response: Opening/closing times of 10-100 milliseconds enable precise control

- Remote operation: Electrical control allows automation and integration with control systems

- Compact design: Small footprint compared to motorized or pneumatic valves of similar capacity

- Reliable operation: Few moving parts result in consistent performance over millions of cycles

- Cost-effective: Lower initial cost and maintenance requirements than most automated valve alternatives

- Binary control: Provides positive shut-off in fully closed position

Practical Limitations

- On/off operation only: Standard solenoid valves cannot provide proportional flow control (though proportional solenoid valves exist at higher cost)

- Power requirement: Requires electrical supply and may need battery backup for fail-safe operation during outages

- Size limitations: Direct-acting valves typically limited to 1-inch diameter; larger sizes require pilot operation with minimum pressure differential

- Heat generation: Continuous-duty coils generate heat that can affect surrounding components

- Sensitivity to contamination: Small orifices can become blocked by debris in dirty systems

- Pressure requirements: Pilot-operated valves need minimum pressure differential to function properly

Emerging Technologies and Future Developments

Solenoid valve technology continues to evolve with advances in materials, electronics, and smart systems integration.

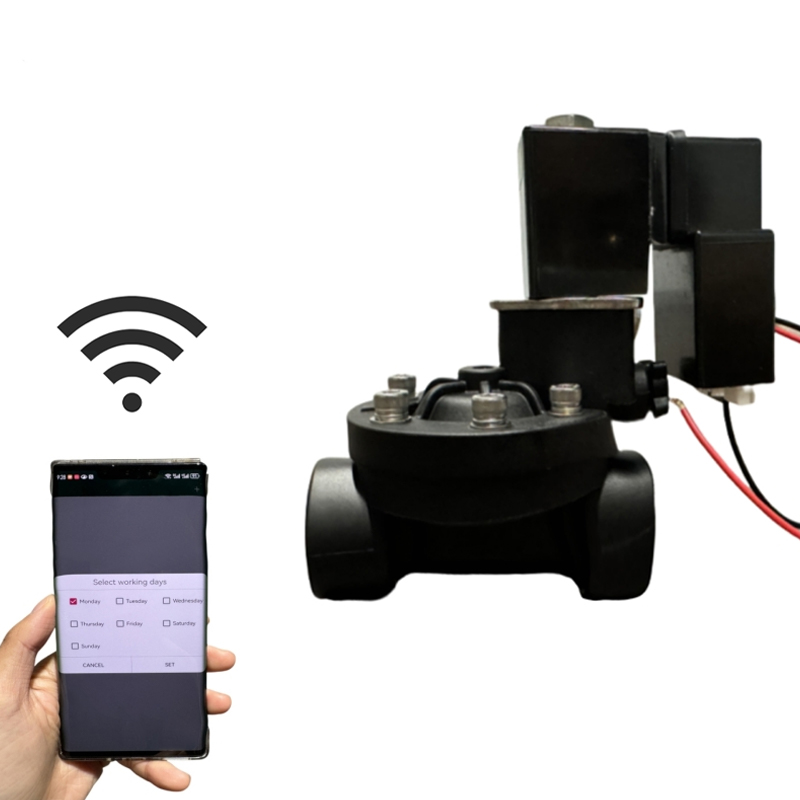

Smart solenoid valves with integrated sensors, diagnostics, and wireless connectivity are gaining traction in Industry 4.0 applications. These valves can report operating status, cycle counts, temperature, and pressure data to central control systems, enabling predictive maintenance that can reduce unexpected failures by 40-60% according to industrial studies.

Low-power designs using permanent magnets and pulse-width modulation reduce energy consumption by up to 90% compared to traditional continuous-duty coils. This advancement is particularly valuable for battery-powered applications and installations with hundreds of valves.

Advanced materials such as high-performance polymers and ceramic components extend operating temperature ranges to 200°C (392°F) and beyond while improving chemical resistance. Nano-coatings on internal surfaces reduce friction and extend seal life by 2-3 times in abrasive fluid applications.

Proportional solenoid valves that provide variable flow control are becoming more affordable and accessible. These valves use electronic drivers to vary the magnetic field strength, allowing precise flow positioning rather than simple on/off control, bridging the gap between solenoid valves and expensive servo-controlled alternatives.

English

English Español

Español